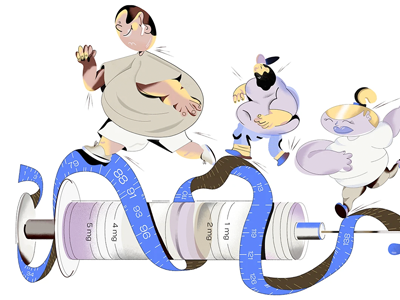

Wegovy, Ozempic and similar weight-loss drugs have become some of the most popular medications in the world. But legions of people are also quitting them. About two-thirds of those in the United States who started taking a drug of this class, known as GLP-1 agonists, in 2021 had stopped using them within a year, according to an industry analysis.

Researchers and clinicians often view GLP-1 agonists as lifelong treatments. But myriad factors can force individuals off the medications. People might lose the means to pay for the costly drugs, experience brutal side effects, be affected by continuing shortages or be offered limited-term prescriptions. The UK National Health Service (NHS), for instance, provides only two years of coverage for people taking the drugs for weight loss.

As the number of people with obesity continues to rise — the World Health Organization estimates that more than one billion people, or one-eighth of the global population, now have obesity — researchers have been answering a few key questions about what happens when people stop taking these medications for weight management.

What happens to weight and health when people quit?

Ozempic and Wegovy are both brand names for the drug semaglutide, which has been prescribed for several years to treat type 2 diabetes (Ozempic) and, since 2021, to those who are overweight or have obesity (Wegovy). The treatment’s aim is to reduce the risk of health complications posed by a large amount of excess body fat, such as heart and liver disease and certain cancers. The drug curbs hunger and food intake by mimicking a hormone, released by the gut after eating, that affects brain regions involved in appetite and reward.

Research has shown what happens when people stop taking GLP-1 agonists. Many regain a substantial amount of what they lost with the help of the medications. The body naturally tries to stay around its own weight point, a pull that obesity specialist Arya Sharma likens to a taut rubber band.

If you take a medication to alter your biology, “the tension of the rubber band is a lot less”, he explains. “But when I take away the medication, that tension is going to come back,” says Sharma, who is based in Berlin and consults part-time for several companies that have an interest in obesity.

For instance, in a trial that studied the effects of withdrawing from the drug, about 800 participants were given weekly injections of semaglutide — as well as making dietary changes, doing exercise and receiving counselling — and lost, on average, 10.6% of their body weight in about 4 months1. Then, one-third of the participants were switched to placebo injections for nearly a year. Eleven months after the switch, those on the placebo had regained almost 7% of their body weight, whereas participants who kept taking semaglutide continued to lose weight. Similarly, participants in an extended semaglutide trial, who lost an average of 17.3% of their body weight after more than one year of receiving the drug and making lifestyle changes, regained about two-thirds of that lost weight after one year without any clinical-trial interventions2.

And an observational study posted in January found that of nearly 20,300 people in the United States and Lebanon who lost at least 2.3 kilograms using semaglutide and who later stopped taking the drug, 44% regained at least 25% of their lost weight after one year (see go.nature.com/3u7nxmj). The work was posted by Epic Research, a journal based in Verona, Wisconsin, that uses an electronic health-record database to rapidly share medical knowledge. The study has not been peer reviewed.

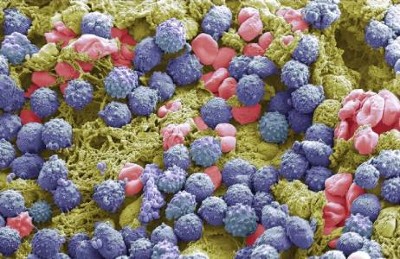

Obesity drugs have another superpower: taming inflammation

But weight wasn’t the only health risk factor that rebounded. In the withdrawal study1, those taking semaglutide beyond four months continued to lower their waist circumferences, says physician-scientist Fatima Cody Stanford at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who consults for several companies developing anti-obesity medications. But “those switched to placebo start to regain in that central region, which is around the key organs where we develop issues like fatty liver disease”, she says.

Other metabolic problems, such as heart disease and insulin resistance, are also linked to excess body fat in the midsection: a larger waistline usually means excess visceral fat, which wraps around organs deep in the abdominal cavity and is more metabolically active than fat that sits under the skin. These health risks, too, can revert to previous levels once the drug is stopped. People who came off semaglutide in clinical trials1,2 often saw a rebound in blood pressure and levels of blood glucose and cholesterol, which had improved while on the medication. (However, some of those measures remained better than those of clinical-trial participants who had never received semaglutide.)

Some people who have lowered their weight with the medication can maintain their new physique through diet and exercise alone, says Sharma. However, these individuals are at high risk of weight rebound if they return to old habits or undergo a stressful situation, he adds.

Still, researchers say, it’s important to acknowledge that not everyone responds to GLP-1 agonists. In one clinical trial, nearly 14% of participants did not lose a clinically meaningful amount of body weight — at least 5% — after more than one year of taking semaglutide3. Some health guidelines recommend stopping the treatment if that threshold has not been met after taking the medication for a few months.

What’s making people stop?

It can be hard to keep taking the medications. Some people experience side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation, that are so extreme that they have to quit. Almost 75% of participants taking semaglutide in the aforementioned clinical trial3 experienced gastrointestinal distress, although most instances were considered mild to moderate. About 7% of participants on the drug quit the trial because of adverse events, gastrointestinal or otherwise.

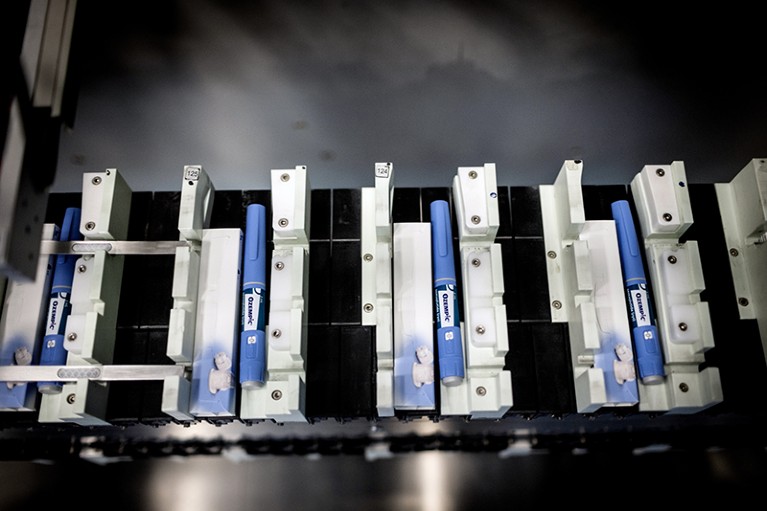

The drug’s manufacturer, Novo Nordisk in Bagsværd, Denmark, has also had trouble keeping up with the demand for semaglutide. Since 2022, the company has announced shortages of both Wegovy and Ozempic; the latter is sometimes prescribed off-label for weight loss.

Some people lose health-insurance coverage for the drugs, leaving them the choice of paying pricey premiums or stopping the treatment, says clinician-scientist Jamy Ard at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston–Salem, North Carolina, who consults for and receives research funding from several companies that have obesity-drug-related programmes. Some of his patients, who paid for the drugs through their private health insurance, could no longer afford them when they retired and switched to the standard US federal health insurance for people aged 65 or older, which does not cover anti-obesity medications for weight-loss management. In the United States, Wegovy’s list price is US$1,350 for one month’s supply.

In some places, the availability of Wegovy and Ozempic has at times lagged behind demand.Credit: Carsten Snejbjerg/Bloomberg via Getty

And in the United Kingdom, where Wegovy was launched last September, those relying on the NHS for semaglutide treatment face a two-year time limit. Guidance issued last March by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that the time constraint comes from a lack of evidence for long-term use and limited access to specialized weight-management services.

That two-year rule “doesn’t make any clinical sense”, says clinician-researcher Alex Miras at Ulster University’s Derry–Londonderry Campus, UK, who receives research and financial support from several companies with an interest in obesity. But he acknowledges that the NICE decision came from cost-effectiveness calculations and the data the decision committee had at the time.

Semaglutide and other anti-obesity medications are available as NHS-funded treatments only at a tier of weight-care management that often requires hospital support and that typically lasts for only two years. Although Miras suspects that most doctors will abide by the time limit on semaglutide use, either to adhere strictly to NICE guidance or because of health-service capacity issues, some might make exceptions depending on disease severity.

Still, he urges the NHS to alter the system so that these medications are available at a lower tier of weight-management services, making the drugs accessible to community-level clinics and lowering the costs for the NHS.

As information about the use of GLP-1 agonists continues to come in, Miras hopes to see “changing policy and changing practice based on our learnings”.

What’s the best way to quit?

Treatment with a GLP-1 agonist requires starting with the smallest dose and gradually increasing the dosage over a few months. This escalating-dose schedule helps to minimize side effects. And, although physicians consider these drugs a lifelong treatment, there’s no biological harm in suddenly stopping.

“There’s not a withdrawal issue or anything like that, like other medications where you have to titrate off,” Stanford says. She advises people to inform their health-care providers of discontinued treatment so that they can keep medical records up to date.

But Ard has encountered anecdotal evidence that suggests otherwise. After quitting GLP-1 agonists, some people have reported higher levels of hunger than before they started treatment. Slowly tapering off the medication, rather than an abrupt stop, he says, “might help with decreasing that sense of rebound hunger”.

The ‘breakthrough’ obesity drugs that have stunned researchers

Sharma also recommends monitoring appetite and weight regained for those who willingly stop the drugs. “Don’t wait till you put 30 pounds back on,” he says. “If you stop and you regain five pounds, maybe that’s when you’ve got to jump back in.” Restarting the medication after time off does require working your way up from the smallest dose again, he says.

For people who have to stop taking GLP-1 agonists for the foreseeable future, continued dietary changes, exercise and mental-health counselling — which should already be in place while on the medication — are a must, Stanford says. People can also try anti-obesity medications that work in other ways, such as orlistat, which reduces how much dietary fat gets absorbed by the body.

But “by the time we’ve gotten to the GLPs, we’ve often unfortunately tried a lot of those”, Stanford says. Another option might be bariatric surgery.

One of the most common reasons that people stop taking their medications is that their weight plateaus, Sharma says, leading them to think that the drugs no longer work. He says that each person will respond to a dose in a different way, and that the dosage might need to be increased to lose more weight.

And many people want to stop once they have reached their goal weight, Ard says. Crossing that finish line gives a sense of completion, he says, especially because weight journeys celebrate milestones. But obesity is a chronic disease that requires lifelong maintenance, including medication, just like high blood pressure or heart disease do. “All we’ve done is modify their physiology,” he notes. “We haven’t cured the disease.”

So much work has gone into developing GLP-1 agonists and getting the medications to people who need them, Ard says. But “we need just as much — if not more — work to be done on what happens after people reach that goal in that weight-reduced state for the rest of their lives”

Obesity drugs have another superpower: taming inflammation

Obesity drugs have another superpower: taming inflammation

The ‘breakthrough’ obesity drugs that have stunned researchers

The ‘breakthrough’ obesity drugs that have stunned researchers

Four key questions on the new wave of anti-obesity drugs

Four key questions on the new wave of anti-obesity drugs